Andrew Rowen, Columbus and Caonabó: 1493–1498 Retold

A new historical novel, Columbus and Caonabó: 1493–1498 Retold, dramatizes Columbus’s invasion of the island of Española on his second voyage and the bitter resistance mounted by its Taíno peoples, led by the Taíno chieftain Caonabó. Based closely on primary sources, the story is told from both Taíno and European perspectives, including through the eyes of Caonabó and Columbus. Caonabó was the first Native chieftain known to organize war against the European settlement of the Americas that began in 1493 and continued for four centuries.

Columbus had left a small settlement of men on Española on his first voyage in 1492. When he returns on the second, he soon realizes that Caonabó’s capture or elimination is key to the island’s conquest. The novel opens before Columbus’s return…

A harbinger of death soared silently across the heavens, silhouetted momentarily by the moon, and abruptly swooped down to alight on a tree rising from the plaza of the small village nestled in the valley below. Its wings and crown shimmered with a silver hue. Caonabó was startled, and he studied the reactions of his lieutenants, huddled naked beside him on an overlooking promontory. They understood owls as guardians of the dead, and they confidently perceived one’s arrival as heralding their attack as a resolution of prior wrongs and portending victory. Caonabó also was confident of victory, but he grimly reflected that none of the other supreme Haitian caciques (chiefs)—or even Anacaona—condoned the attack.

He peered down to survey the village layout with a general’s acumen, seeking to determine where the pale men slept. In his midforties, Caonabó had achieved renown decades before as Haiti’s greatest warrior by vanquishing Caribe raiders, ascending to rule his chiefdom of Maguana by virtue of his valor. Weeks earlier, he’d received a runner dispatched by Guacanagarí, the supreme cacique of Marien to the northwest, warning that eleven pale men were wandering south to befriend him, bent on trading for gold, and that Guacanagarí had refused to escort them, knowing Caonabó would be hostile. Caonabó’s scouts had tracked the band to this village, reporting that the pale men straggled through his chiefdom with an unruly malevolence—seizing food from his subjects, disparaging the nobility of his local caciques, rudely displacing everyone from their bohíos (homes, houses), and luridly entreating women and girls.

The village cacique had been a loyal friend for years. Caonabó surmised that the pale men had expelled him from his caney (a chieftain’s home), the band’s leaders usurping it to sleep inside, with the remainder commandeering the adjacent bohíos circling the plaza. He ordered his lieutenants to execute the pale men summarily, without torture, and deployed them to lead his warriors in stealth left and right on the valley’s hillside rims to surround the village. They’d strike when the moon dipped to the hill line and the village slipped into darkness, just before dawn’s twilight.

The jagged streaks oiled in red and black on his men’s olive-brown skin occasionally flickered through the underbrush as they advanced, and Caonabó observed the owl rotating its head nearly a full turn to scrutinize their movement. Victory in battle rarely was inevitable, and, for an instant, he contemplated whether the owl foretold his own men’s death. The intruders below were hopelessly outnumbered, but their weapons were reputed to be fearsome, and it was possible that they—or their spirits—would prove formidable opponents.

Caonabó took final stock of the grave command that now was upon him. The pale men had first arrived off Haiti’s northern coast less than a year before, venturing in an enormous vessel of unknown construction. Many of his subjects believed them to be spirits rather than men. Caonabó’s nitaínos (noblemen) had traded gold with them profitably for a week, obtaining marvelous objects previously unseen, as had other supreme Haitian caciques. Pale men borne in two other vessels had visited Guacanagarí’s chiefdom to trade for gold, as well. But one of those vessels had sunk, and Guacanagarí had befriended the pale men’s leader and permitted him to establish a settlement near Guacanagarí’s town. More than three dozen pale men had lived there since their leader departed to his homeland.

Caonabó grimaced, vexed by a pang of scorn directed at Guacanagarí, as the settlement had proved a disaster, the pale men growing uncivil, lawless, and contemptuous of Taíno customs and spirits. They had slid to indolence, too lazy to grow, hunt, or fish for their own food, stealing it instead. They craved gold insatiably, and many had grown too impatient to trade for it, resorting to looting jewelry and ripping gold inlays from venerated face masks. Their lust for Taíno women had surged unrestrained—regardless of countless warnings to desist—and rape now constantly threatened. They had even murdered two of their own.

A soft light glowed dimly on the opposite hillside, a lieutenant fluttering a cotton satchel of cocuyos (large fireflies), signaling encirclement was complete. Caonabó shook his own sack of cocuyos in return, and a lone warrior began to descend to the village, deftly avoiding the rustle of leaves and trample of stalks that would alert his presence. His mission, to the extent stealth permitted, was to alert villagers sleeping in bohíos near the plaza to depart for the forest perimeter just before the attack began…

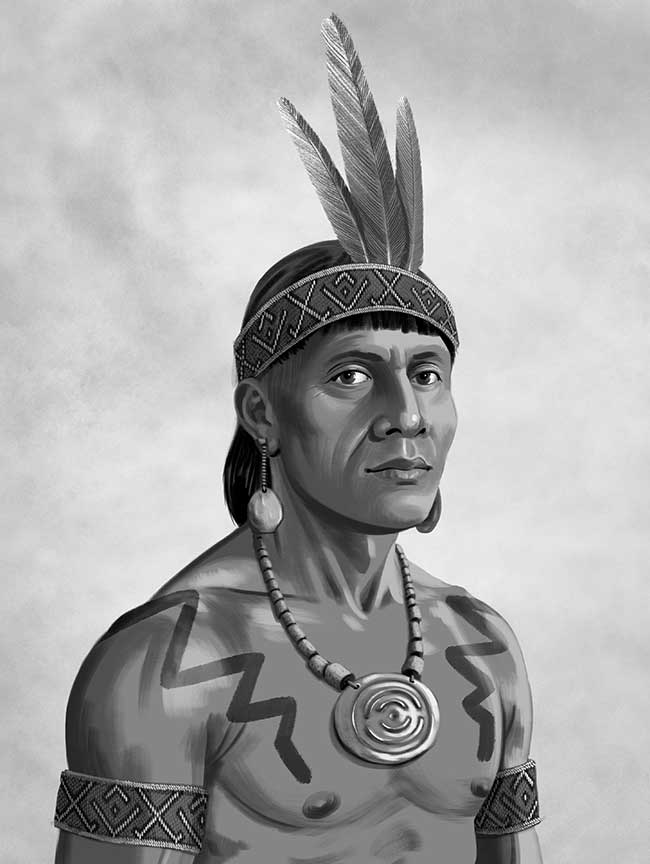

The novel depicts the ensuing clash of European and Taíno soldiers, cultures, and religions; the enslavement of Taíno captives; Columbus’s imposition of tribute obligations; the initial Christian missionary efforts; the ravage of epidemic disease transmission; and Columbus and Caonabó’s hostile face-to-face conversations. It contains forty-two maps and illustrations, including a sketch of Caonabó (drawn by the Dominican illustrator Boris De Los Santos), and its cover page depicts the critical battle of “Santo Cerro” in March 1495. For more information and reviews, go to https://www.andrewrowen.com.

>

>