JFK and Vietnam

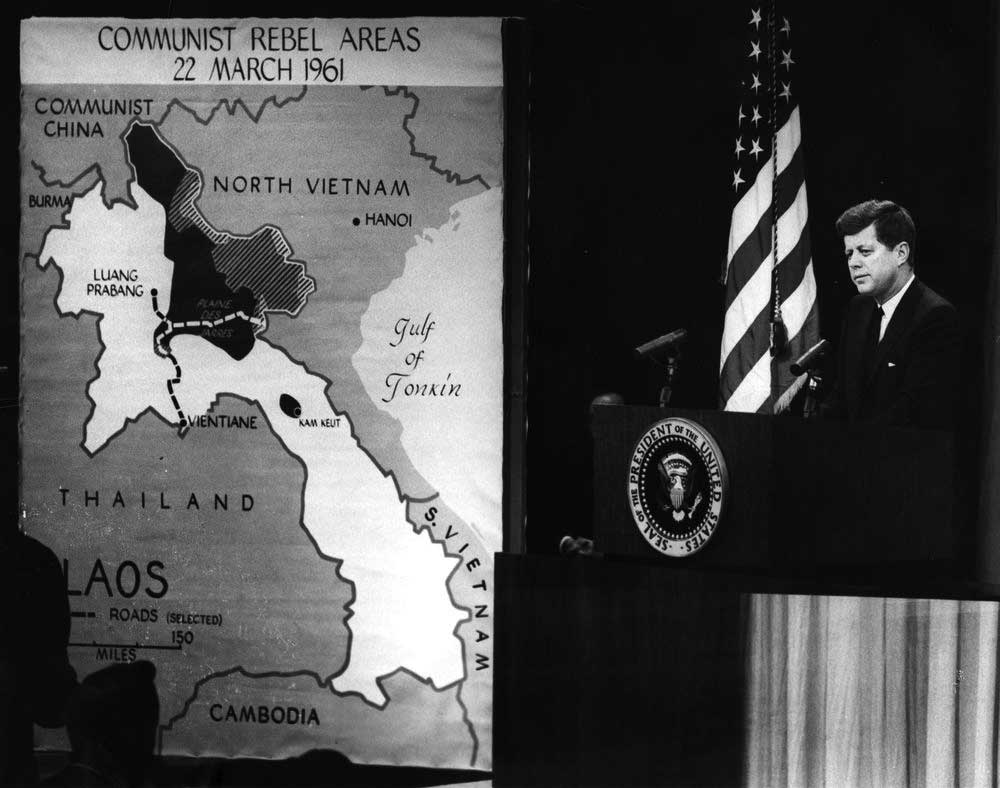

Press Conference March 23

When President Kennedy took office, the initial problem in South East Asia was Laos. The US agreed to a neutral Laos. This agreement was negotiated in Geneva. Soon, however, it became apparent that the most serious Vietnam problem was the Communist attacks in South Vietnam. Kennedy was reluctant to commit US forces to Vietnam, but was more reluctant to allow it to fall into Communist hands. In a pattern that was to repeat itself throughout the war, Kennedy heard a eries of reports that the war could be won if only... In the end, the US encouraged an army revolt against South Vietnamese leader Diem, further committing the US to South Vietnam.

The question of how to handle the situation in Vietnam vexed President Kennedy from his first days in office. Vietnam had been a French Colony. In 1954, the French were forced to give the country independence, as a result of a guerilla war, led primarily by Communists. Under the terms of an accord reached in Geneva, the country was to be split between a Communist North and a non-Communist (largely Catholic) South. The terms of the agreement called for nationwide elections to be held to unify the country. This provision was never signed by the provisional government of South Vietnam.

Two years later, when no elections had been held, the insurgency that had initially fought against the French, began again to fight, this time against the South Vietnamese government. The insurgents demanded the removal of the South Vietnamese government and the reunification, of both North and South, under a Communist regime.

Kennedy had always questioned the imperative of American military involvement in South East Asia. In 1953, while serving in the Senate, Kennedy suggested that US war aid to France be contingent on its promoting the Independence of Indo-China. In a 1957 Senate speech he stated: " The most powerful single force in the world today is neither Communism nor Capitalism, neither the H-bomb, nor the guided missile. It is man's eternal desire to be free and independent. "

During the transition between his election and his Presidential inauguration, Kennedy was advised by Eisenhower to counter Communist aggression in Cambodia, South Vietnam and Laos. When Kennedy first took office, Laos was central to his agenda, and Vietnam was not. However, while the situation in Laos headed toward a stalemate between three major factions, including the Communists; the situation in Vietnam was getting worse.

Soon after taking office, Kennedy received a briefing by Edward Lansdale, who had been sent by the Defense Department to evaluate the situation in Vietnam. Lansdale reported to Kennedy that Vietnam was in critical condition and needed emergency treatment. Kennedy inherited a commitment of 600 American military advisors stationed in Vietnam. Kennedy authorized funding for additional training and maintenance of South Vietnamese troops. He created a task force for Vietnam. When asked if he was willing to send combat troops to stop the spread of Communism in Vietnam, Kennedy avoided answering the question. He sent Vice President Johnson to the region to " show the flag" and demonstrate US support for the South Vietnamese government.

By summer, after the failed summit in Vienna and the fiasco of the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy felt he could not walk away from Vietnam. But he remained very reluctant to commit US troops. An April 28th memo by Ted Sorenson, said to reflect Kennedy's thinking on Vietnam stated, " There is no clearer example of a country that cannot be saved unless it saves itself€“ through increased popular support; governmental, economic and military reforms and reorganizations; and the encouragement of new political leaders" .

In September 1961 President Kennedy ranked Vietnam as the number one threat to world stability in his speech to the UN. In late October 1961, the President sent a task force led by General Taylor and Walt Rostow to evaluate the situation in Vietnam. They compiled a 52-page report that called for the introduction of 6,000-8,000 US combat troops. For the first time, the report brought up the possibility of ousting South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem. Recommendations from The Joint Chiefs and the Defense Department went beyond that, suggesting the US needed to send up to 200,000 troops to counter the Communist threat. President Kennedy was not especially receptive to these recommendations. Kennedy told The New York Times journalist, Arthur Krock, that, " United States troops should not be involved on the Asian mainland. The United States can€™t interfere in civil disturbances, and it is hard to prove that this wasn€™t largely the situation in Vietnam. "

Opposing the military's recommendations were Senate Majority leader Mike Mansfield, Kenneth Galbraith, George Ball and Averell Harriman. Kennedy refused to approve deployment of combat troops, but stepped up aid to the Diem regime and ordered a substantial increase in the number of advisors in Vietnam. In return, Kennedy demanded from Diem that the US advisors have a role in making all the important decisions. He also ordered the military to prepare contingency plans for the deployment of military combat forces.

By February 1962, there were 3,500 US combat advisors in Vietnam. They accompanied Vietnamese troops on missions which were to inexorably lead to US troops being drawn into combat. But, in early 1962 when the President was asked at a press conference if US troops were involved in combat, Kennedy gave a one word answer: " No. " The President, ambivalent about US involvement in Vietnam, feared an increased commitment.

In June 1962, Kennedy successfully convinced the Soviets to pressure the Laotian Communists, the Pathet Lao, to return to negotiations and enter into a coalition government, thereby avoiding a confrontation over Laos. Kennedy was hoping to expand this agreement to extend to the rest of Southeast Asia. Kennedy asked Averell Harriman Assistant US Secretary of State, and his deputy William Sullivan to meet with the Vietnamese Foreign Minister with hopes of opening negotiations. They reported back that no progress had been made.

However, the reports from the field were positive. Defense Secretary McNamara made his first fact-finding trip to Vietnam and returned optimistic, stating that the tide had turned. Positive reports continued to arrive, including one by General Maxwell Taylor who spoke glowingly of the success of the strategic hamlet program. The reports were so encouraging that Kennedy asked McNamara to draw up plans for the eventual withdrawal of US forces. US correspondents on the ground were not nearly as optimistic, but Kennedy discounted their warnings.

By the end of the year Kennedy was getting ever-more conflicting information on the situation in Vietnam. At a press conference in December1962 he stated: " As you know, we have about 10 or 11 times as many men there as we had a year ago. We€™ve had a number of casualties and we have put an awful lot of equipment. We are going ahead with the strategic hamlet program. But there is a great difficulty in fighting a guerrilla war, especially in terrain as difficult as South Vietnam. So we don't see an end of the tunnel, but I must say I don€™t think it is darker than it was a year ago, and in some ways lighter. "

In early 1963, Kennedy sent the head of the Intelligence Division of the State Department, Roger Hilsman, to assess the situation in Vietnam. Hilsman returned with a sobering report, that although things were going better than they had been a year earlier, winning the war was going to take longer and be much harder than the military had been reporting. By this time, there were 16,000 US advisors in Vietnam. Kennedy seemed to become even more skeptical of the US ability to obtain its objective in Vietnam and wanted to begin planning for a withdrawal. This withdrawal would come only after the November 1964 elections, for Kennedy feared the political fallout of a precipitous withdrawal from Vietnam. In the spring of 1963, South Vietnamese leader Diem provoked a crisis with the Buddhist minority. That confrontation undermined much of the progress made in the preceding months in the conflict with the Communists. Diem's confrontation with the Buddhists crystallized the opposition to his rule and the CIA began planning to have him removed from office in a US-supported coup. Kennedy was reluctant to go along with a coup, but eventually agreed to allow the planning to go forward.

Kennedy tried to avoid the day of reckoning with Diem by pressuring him to reform. Unfortunately, reports from Vietnam were turning more and more pessimistic and Kennedy was becoming convinced of the futility of the actions. Kennedy began to push for a withdrawal plan. One was put forward that would include the symbolic withdrawal of 1,000 troops by the end of 1963. In a news conference held at the end of October, Kennedy publicly confirmed the plan.

Meanwhile, a new plan had been developed to oust Diem. Kennedy gave his reluctant approval, and in the early morning hours of November 1, Vietnamese Army forces staged the coup. When Diem asked for US help it was denied, as was his request for transport to leave the country. Diem and his wife were killed while in custody of the Vietnamese troops. Kennedy was genuinely upset at the deaths. In a recording he made for posterity on November 4, he took personal responsibility for their deaths. The day he left for Texas, November 21, 1963, President Kennedy told Senator Mike Mansfield that in early 1964 he " wanted to organize an in-depth study of every possible option we've got in Vietnam, including how to get out of there. "

Sadly, two days later, President Kennedy was assassinated. The vexing question of how to handle the situation in Vietnam would never be solved by Kennedy.

>

>