Limited vs Full Enfranchisement: Race in the Struggle for Women’s Suffrage

By Daniel Franklin

I

In a troubled year, on August 26 millions will honor the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment which will give cause for celebration and reflection.

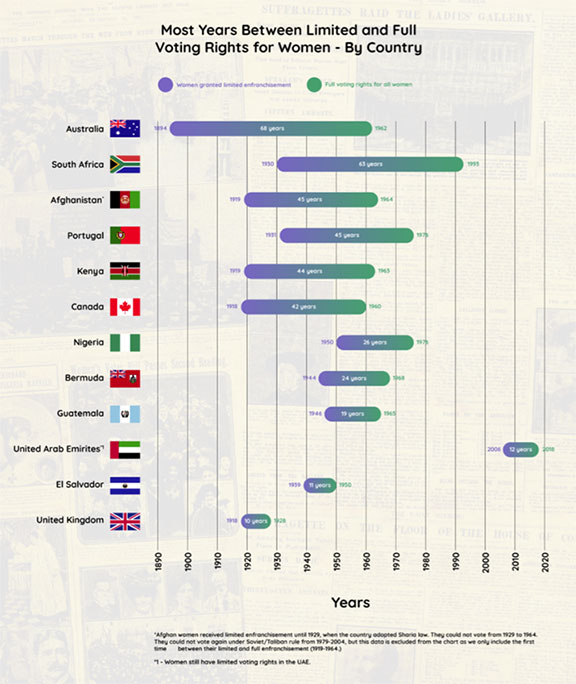

America was the 25th country worldwide to award women the vote in 1920, and this puts it in the top 12% all time, far ahead of many other Western democracies when looking at awarding full enfranchisement. In this article, we’ll look at the somewhat marred history of those countries with the biggest gap between awarding limited, and full, enfranchisement throughout history.

First, it’s important to acknowledge how race and the vote for women were inextricably linked from the mid-1800s.

When the first mass women’s suffrage petition, containing 1,500 women’s signatures, was presented to the House of Commons in England in June 1866, the name of one black woman was included. Sarah Parker Remond was an African American who had been giving anti-slavery lectures in England since early 1859. Remond’s stance on suffrage mirrored that of her anti-slavery message, all people deserved the basic right to be viewed as equal within any society.

Fellow abolitionist, and former slave, Sojourner Truth was touring the United States at the same time, giving lectures promoting equality and challenging the concepts of gender and race inferiority. In 1867, one year after the petition in the UK was presented to Parliament, Truth was lecturing at the American Equal Rights Association, solidifying her stance that the black vote and the women’s vote should be granted together.

“I feel that I have the right to have just as much as a man. There is a great stir about coloured men getting their rights, but not a word about the coloured women; and if coloured men get their rights, and coloured women not theirs, the coloured men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before.” - Sojourner Truth

Truth was eerily prophesizing what would eventually take place in America. Black men were awarded the vote with the 15th Amendment, but women had to wait another 50 whole years. Yet, when the vote did come, it came for all women, and actually allowed black women in the USA to vote before the majority of women in many other Western countries.

Australia (68 years between limited and full enfranchisement)

After New Zealand granted voting rights to women in 1892, Australia followed their neighbors soon after, in 1894. However, the privilege was restricted to colonials only. Aboriginal Australians would have to wait until 1962 to be awarded the vote. Australia has a chequered history with its indigenous population, and the 68 years they had to wait is the longest time between limited and full enfranchisement in history.

Canada (42 years)

Similar to Australia, indigenous Canadian women were largely kept silent when it came to voting. Canada awarded enfranchisement after the war in 1918 but this was to whites only. Even after Inuit women were granted the vote in 1960, it would take two more years before ballot boxes were even brought to the Arctic.

The struggle was similar for Asian women (and men) in Canada, who had to wait until 1948 to receive the vote.

United Kingdom (10 Years)

Following the end of World War One, as many of the returning soldiers would not be eligible it was felt that all men had earned the right to vote. When the Representation of the People Act of 1918 was passed, the first women were also finally given the vote. There was no specific caveat on the right to vote regarding race, though the women eligible to vote must be over the age of 30 and the owner of (or wife to the owner of) property. This therefore excluded almost all non-whites from voting.

The majority of women of color would need to wait a further ten years before they could vote in Britain as young and working class women would only be included in the enfranchisement of the vote within the Representation of the People Act (1928). All adults over the age of 21 were then eligible to vote throughout the UK, regardless of status, race or gender.

When it comes to the length of time between countries awarding limited and full enfranchisement, it is clear that race was, in most cases, the sole contributing factor.

>

>