Bacon Rebellion

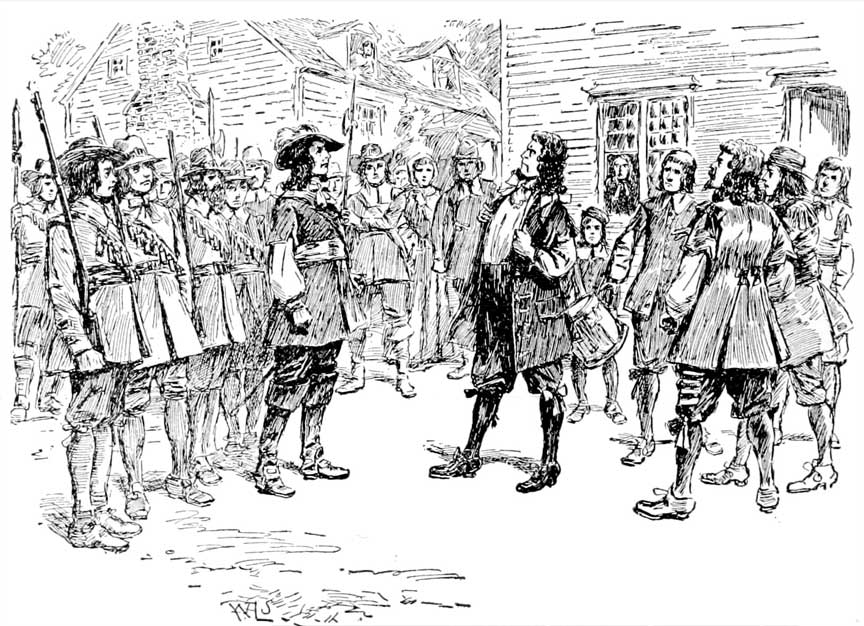

Bacon and Berkely

Hostilities escalated between the Indians around the Virginia colony and the colonists. Virginia governor, William Berekely, refused to empower settlers to go after the Indians. James Bacon, a recent immigrant, led a force against the Indians. He was declared a traitor by Governor Berekely and jailed. After being freed, Bacon raised an army of supporters, who took control, forcing the governor to flee. The rebellion collapsed when Bacon died suddenly.

Bacon's Rebellion was caused by a number of issues. Economic problems, such as declining tobacco prices, growing commercial competition from Maryland and the Carolinas, an increasingly restricted English market, and the rising prices from English manufactured goods (mercantilism) caused problems for the Virginians. There were heavy English losses in the latest series of naval wars with the Dutch and, closer to home, there were many problems caused by weather.

In July 1675, Doeg Indians led a raid on the plantation of Thomas Mathews, located in the Northern Neck section of Virginia, near the Potomac River. Several of the Doegs were killed in the raid. This began in a dispute over the nonpayment of some items Mathews had apparently obtained from the tribe. The situation became critical when in a retaliatory strike by the colonists. The colonists attacked the wrong Indians, the Susquehanaugs. This caused large scale Indian raids to begin.

To stave off future attacks and to bring the situation under control, Governor Berkeley ordered an investigation into the matter. He set up what was to be a disastrous meeting between the parties. The meeting resulted in the murders of several tribal chiefs. Throughout the crisis, Berkeley continually pleaded for restraint from the colonists. Some, including Bacon, refused to listen. Nathaniel Bacon disregarded the Governor's direct orders by seizing some friendly Appomattox Indians for "allegedly" stealing corn. Berkeley reprimanded Bacon, which caused the disgruntled Virginians to wonder which man had taken the right action.

Further problems developed from Berkeley's attempt to find a compromise. Berkeley's policy was to preserve the friendship and loyalty of the subject Indians while assuring the settlers that they were not hostile. To meet his first objective, the Governor relieved the local Indians of their powder and ammunition. To deal with the second objective, Berkeley called the "Long Assembly", in March 1676. Despite being judged corrupt, the assembly declared war on all "bad" Indians and set up a strong defensive zone around Virginia with a definite chain of command. The Indian wars which resulted from this directive led to the high taxes, to pay the army and to the general discontent in the colony for having to shoulder that burden.

The Long Assembly was accused of corruption because of its ruling regarding trade with the Indians. Not coincidentally, most of the favored traders were friends of Berkeley. Regular traders, some of whom had been trading independently with the local Indians for generations, were no longer allowed to trade individually. A government commission was established to monitor trading among those specially chosen and to make sure the Indians were not receiving any arms and ammunition. Bacon, one of the traders adversely affected by the Governor's order, accused Berkeley publicly of playing favorites. Bacon was also resentful because Berkeley had denied him a commission as a leader in the local militia. Bacon became the elected "General" of a group of local volunteer Indian fighters because he promised to bear the cost of the campaigns.

After Bacon drove the Pamunkeys from their nearby lands, in his first action, Berkeley exercised one of the few instances of control over the situation that he was to have. He rode to Bacon's headquarters at Henrico with 300 "well armed" gentlemen. Upon Berkeley's arrival, Bacon fled into the forest with 200 men in search of a place more to his liking for a meeting. Berkeley then issued two petitions declaring Bacon a rebel and pardoning Bacon's men, if they went home peacefully. Bacon would then be relieved of the council seat that he had won for his actions that year. However, he was to be given a fair trial for his disobedience.

Bacon did not, at this time, comply with the Governor's orders. Instead, he next attacked the camp of the friendly Occaneecheee Indians on the Roanoke River and took their store of beaver pelts.

In the face of a brewing catastrophe, Berkeley, to keep the peace, was willing to forget that Bacon was not authorized to take the law into his own hands. Berkeley agreed to pardon Bacon if he turned himself in. Then Bacon could be sent to England and tried before King Charles II. It was the House of Burgesses, however, who refused this alternative, insisting that Bacon must acknowledge his errors and beg the Governor's forgiveness. Ironically, at the same time, Bacon was then elected to the Burgesses by supportive local landowners sympathetic to his Indian campaigns. Bacon, by virtue of this election, attended the landmark Assembly of June 1676. It was during this session that he was mistakenly credited with the political reforms that came from this meeting. The reforms were prompted by the population, cutting through all class lines. Most of the reform laws dealt with reconstructing the colony's voting regulations, enabling freemen to vote, and limiting the number of years a person could hold certain offices in the colony. Most of these laws were already on the books for consideration, well before Bacon was elected to the Burgesses. Bacon's only cause was his campaign against the Indians.

Upon his arrival for the June Assembly, Bacon was captured. He was taken before Berkeley and the council. He was made to apologize for his previous actions. Berkeley immediately pardoned Bacon and allowed him to take his seat in the assembly. At this time, the council still had no idea how much support was growing in defense of Bacon. The full awareness of that support hit home when Bacon suddenly left the Burgesses in the midst of heated debate over Indian problems. He returned with his forces to surround the statehouse. Once again, Bacon demanded his commission, but Berkeley called his bluff and demanded that Bacon shoot him. Bacon refused.

Berkeley granted Bacon his previous volunteer commission, but Bacon refused it and demanded that he be made General of all forces against the Indians. Berkeley emphatically refused and walked away. Tensions ran high as the screaming Bacon and his men surrounded the statehouse, threatening to shoot several onlooking Burgesses if Bacon was not given his commission. Finally, after several agonizing moments, Berkeley gave in to Bacon's demands for campaigns against the Indians without government interference. With Berkeley's authority in shambles, Bacon's brief tenure as leader of the rebellion began.

Even in the midst of these unprecedented triumphs, Bacon was not without his own mistakes. He allowed Berkeley to leave Jamestown in the aftermath of a surprise Indian attack on a nearby settlement. He also confiscated supplies from Gloucester and left them vulnerable to possible Indian attacks. Shortly after the immediate crisis subsided, Berkeley briefly retired to his home at Green Springs and washed his hands of the entire mess. Nathaniel Bacon dominated Jamestown from July through September 1676. During this time, Berkeley did come out of his lethargy and attempt a coup, but support for Bacon was still too strong and Berkeley was forced to flee to Accomack County on the Eastern Shore.

Feeling that it would make his triumph complete, Bacon issued his "Declaration of the People" on July 30, 1676, which stated that Berkeley was corrupt, played favorites and protected the Indians for his own selfish purposes. Bacon also issued his oath which required the swearer to promise his loyalty to Bacon in any manner necessary (i.e., armed service, supplies, verbal support). Even this tight reign could not keep the tide from changing again. Bacon's fleet was first and finally secretly infiltrated by Berkeley's men and finally captured. This was to be the turning point in the conflict because Berkeley was once again strong enough to retake Jamestown. Bacon then followed his sinking fortunes to Jamestown and saw it heavily fortified. He made several attempts at a siege, during which he kidnapped the wives of several of Berkeley's biggest supporters, including Mrs. Nathaniel Bacon Sr., and placed them upon the ramparts of his siege fortifications while he dug his position. Infuriated, Bacon burned Jamestown to the ground on September 19, 1676. (He did save many valuable records in the statehouse.) By now his luck had clearly run out with this extreme measure and he began to have trouble controlling his men's conduct, as well as keeping his popular support. Few people responded to Bacon's appeal to capture Berkeley, who had since returned to the Eastern Shore for safety reasons.

On October 26th, 1676, Bacon abruptly died of the "Bloody Flux" and "Lousey Disease" (body lice). It is possible his soldiers burned his contaminated body because it was never found. (His death inspired this little ditty; "Bacon is Dead, I am sorry at my hart, That lice and flux should take the hangman's part".)

Shortly after Bacon's death, Berkeley regained complete control and hanged the major leaders of the rebellion. He also seized rebel property without the benefit of a trial. All in all, twenty-three persons were hanged for their part in the rebellion. Later after an investigating committee from England issued its report to King Charles II, Berkeley was relieved of the Governorship and returned to England where he died in July 1677.

>

>