Reconstruction Act

The end of the Civil War necessitated a decision specifying the terms by which the South could be readmitted to the Union. Both Lincoln and Johnson took the position that the South had never left the Union and therefore the question of readmission was moot. The Congress had other ideas and passed a series of laws imposing military control over the South and provided rights to African Americans

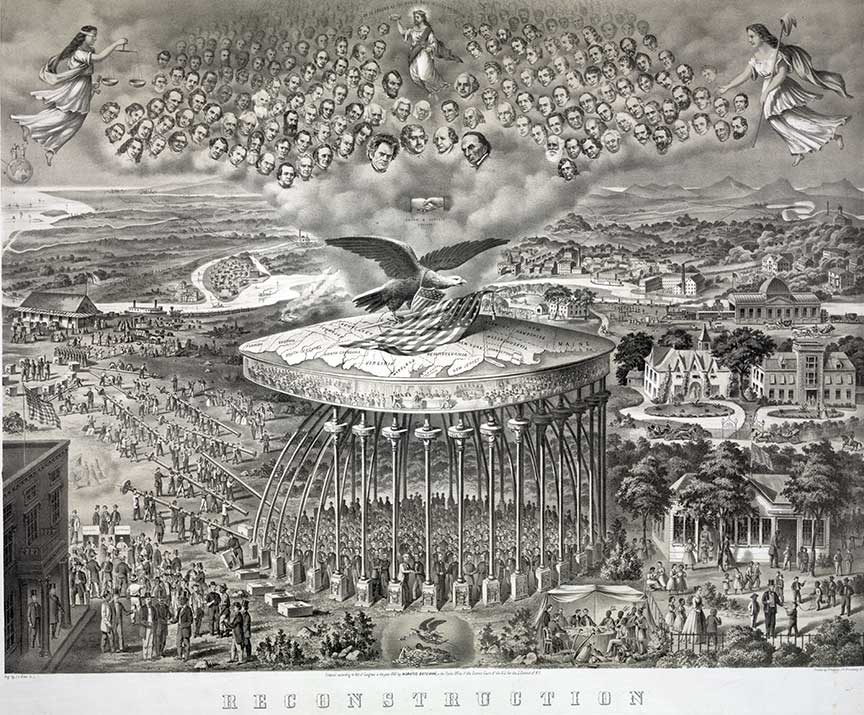

The Reconstruction Act, passed in 1867 following the American Civil War, was a pivotal piece of legislation aiming to rebuild the South and fully integrate former slaves into American society. This act divided the ten Southern states that had yet to be readmitted into the Union into five military districts, each overseen by a Union general. To be readmitted to the Union, each state was mandated to draft a new state constitution for Congressional approval, grant the right to vote to all male citizens irrespective of race or previous servitude, and ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, which provided citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the U.S., including former slaves.

One of the most profound impacts of the Reconstruction Act was the enfranchisement of African American men. This newfound right to vote and engage in the political process saw a surge in the election of African American officials at multiple governmental levels. In fact, many southern states witnessed African Americans being elected to state legislatures, and a few even sent African American representatives to the U.S. Congress.

Parallel to this political transformation, there was an enthusiastic push among freedmen for education. Northern missionary associations and entities like the Freedmen's Bureau facilitated the establishment of schools for African Americans throughout the South. Many newly freed individuals viewed education as the bedrock of their improved lives and a pillar of their sustained freedom.

However, economic autonomy proved elusive. With slavery's end, the challenge was to find sustainable economic opportunities. Many African Americans turned to sharecropping, leasing plots of land to cultivate in return for a share of the crops. Although this system was often exploited by white landowners, it was a beginning toward economic self-determination.

Yet, this period of transformation wasn't devoid of social challenges. White resentment towards African Americans' newfound freedoms grew significantly. This resentment gave rise to white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, which embarked on campaigns of violence and intimidation to curtail black advancements.

Amid these societal shifts, African Americans began building their own institutions. Churches emerged as more than just spiritual sanctuaries; they became community mobilization centers, educational hubs, and political platforms.

But as time wore on, the national commitment to the principles of Reconstruction started to wane. The contentious presidential election of 1876 effectively marked the end of military Reconstruction in the South. As federal troops pulled out, many of the hard-won gains for African Americans began to erode, paving the way for the oppressive era of Jim Crow laws and racial segregation that would dominate the South into the 20th century.

In essence, while the Reconstruction Act sought to reshape Southern society and offer unprecedented opportunities for African Americans, its legacy is a tapestry of significant advancements intertwined with challenges and setbacks.

>

>