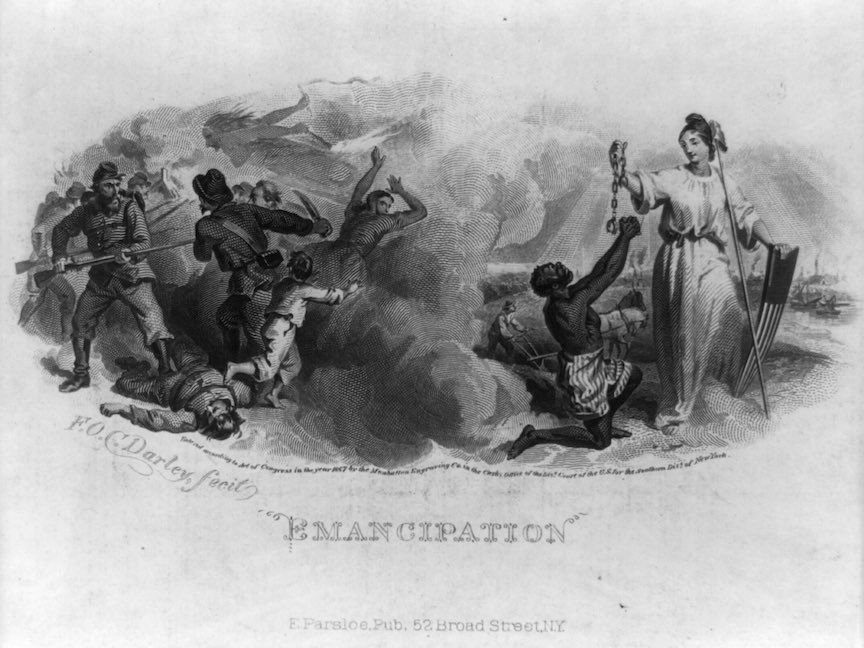

1863 Emancipation Proclamation

On January 1st, 1863, President Lincoln issued a Proclamation of Emancipation which freed all of the slaves in those states under rebellion who had not yet been conquered by the Northern armies. Although the proclamation did not in fact free even one slave at that moment, it heralded the end of slavery.

The Emancipation Proclamation was formally issued on January 1, 1863, but a preliminary proclamation had been made earlier on September 22, 1862, following the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam. The proclamation declared that all slaves in Confederate-held territory were free, fundamentally altering the character of the Civil War and paving the way for the abolition of slavery in the United States.

The issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order, grounded in Lincoln’s authority as the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. Specifically, the proclamation applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the border states as well as areas of the Confederacy already under Union control at the time of the proclamation. Thus, its immediate impact was limited as it did not free a single slave; however, it was a crucial step towards the complete abolition of slavery, subsequently achieved through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865.

The proclamation had a number of profound impacts. First, it redefined the Union war effort. While the initial goal of the North had largely been to preserve the Union, the Emancipation Proclamation made the abolition of slavery an explicit war aim. Second, the proclamation had a substantial psychological impact, providing a moral impetus to the Union cause and making foreign intervention on behalf of the Confederacy less likely. Third, it had immediate and long-lasting impacts on African Americans, both enslaved and free. By turning Union lines into a destination for freedom, it led to mass movements of African Americans towards Union camps. Moreover, it allowed for the enlistment of African American soldiers into the Union Army, with approximately 200,000 black soldiers serving by the end of the war.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not immediately free all slaves, it changed the legal status of millions of enslaved people, if not practically then symbolically. As Union armies advanced into Confederate territory, the proclamation had the effect of legally liberating enslaved people in those areas, thus making the Union Army a force for liberation as well as for the suppression of the rebellion. By the end of the Civil War, the proclamation, along with the Thirteenth Amendment, led to the emancipation of nearly four million enslaved African Americans.

Critics argue that Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation more as a war measure than out of an ideological commitment to abolish slavery. However, it's worth noting that the proclamation was a risky political move, with an uncertain public reaction. Lincoln was acutely aware of the various political, military, and moral dimensions of his act. He understood the limitations of his proclamation but viewed it as a necessary step that would pave the way for complete emancipation.

In sum, the Emancipation Proclamation was a landmark moment in American history, one that expanded the goals of the Civil War and paved the way for the eventual abolition of slavery in the United States. While it had its limitations, both in scope and immediate impact, it had profound and far-reaching effects. It redefined the purpose of the Civil War, deterred foreign intervention in favor of the Confederacy, allowed the enlistment of African Americans in the Union Army, and fundamentally altered the lives and future of millions of enslaved African Americans.

>

>